EL MÚSICO

GUSTAVO “EL CUCHI” LEGUIZAMON

(1917 – 2000)

Gustavo Leguizamón fue un hombre culto y sensible que brilló como pianista y compositor, pero también fue poeta, abogado, profesor y un agudo crítico social.

Nació en 1917 en la ciudad de Salta. Hijo de un contador fanático de la ópera y de una mujer que heredó la costumbre de silbarles a los pájaros para que la siguieran.

Tenía pocos meses de vida y preocupaba por su delgadez. Fue en esa época donde en una ocasión ofrecieron a su madre unos chanchos para la compra. «¡Pero están flacos como este cuchi!», dijo, mirando a su hijo. En ese instante el niño quedó rebautizado, y para todos sería “el Cuchi”.

Cuando a los dos años se enferma de sarampión, su padre le regala una quena, haciéndolo musiquero, antes casi de que aprendiera a hablar. Después, siempre de oído, la emprendería con la guitarra y el bombo, hasta acabar en el piano.

Cuando tenía veinte años ya era todo un músico. Aún así, le comunica a su padre que estudiaría Derecho. El hombre se encrespó, su idea era que su hijo fuera a París para perfeccionarse, pero el Cuchi, que se deleitaba con tener una historia al revés de los mandatos y los convencionalismos, no hizo caso y marchó a La Plata, donde obtuvo el título de abogado.

Cantó en el coro universitario y jugó rugby. Mas tarde, ya en Salta, fue profesor de historia y filosofía y también asesor cultural de gobierno. Y como si fuera poco, se dio tiempo, para ser Diputado Provincial, protagonizando en la Legislatura debates memorables para propender al “descongelamiento cerebral”. Polemista filoso y defensor de pobres decía: «¿Cómo podés matar de hambre a la gente y pensar que hay que pisar los cadáveres de los sumergidos para que la patria financiera no se despeine?».

Amó a las mujeres de una manera que erizaría los pelos de una feminista: «Las mujeres del artista tienen que ser santas de la vida, es decir, grandes aristócratas o maravillosas mujeres del pueblo”, ésas que según él «engualichan» con la comida como preludio de un sueño que no es tal sino otra cosa. Ateo romántico, se casó por Iglesia con Ema Palermo con quien tuvo cuatro hijos.

Fue un gran lector, un «moderno» en Salta, un hombre ilustrado. Prestó gran atención a las manifestaciones de todas las vanguardias artísticas, en la literatura, la música, en la pintura y el teatro.

Carismático, el Cuchi siempre se hizo notar. Irónico y provocativo, cuentan que una vez lo encontraron leyendo al Che Guevara en el selecto Club 20, en tiempos de la dictadura militar. Burlón y ocurrente, era el primero en festejar sus propios chistes con una sonora carcajada.

Ejerció durante treinta años la abogacía, hasta que decidió dejarla. Confesaba: “Hacer música no me alcanza para vivir pero me hace vivir. Mira lo que son las cosas. Antes cuando era abogado vivía de la discordia y ahora de la alegría. A la vejez no me queda más que hacer música hasta que me toque pulsear con la nada. Le voy a ganar a la nada porque ella estará allí en lo suyo y yo estaré silbando alguna cosa».

Para el Cuchi la música tuvo una dimensión eminentemente vital y alegre, saltó sobre el pentagrama, pulsó cuerdas, sopló en maderas, cobres y cuernos, digitó teclados, a pura “oreja”. Organizó conciertos de campanarios de iglesias, y hasta intentó un concierto de locomotoras, fascinado por lo que él llamaba “ese instrumento maravilloso”. Admiró a los animales, se tomó tiempo para escuchar sus ritmos y melodías, y aprendió de ellos

Su fuerza andariega y juguetona lo llevó a entreverarse en la vida popular, en sus fiestas y coplas. Su trato y amistad con los poetas fue una de sus pasiones. De todos ellos, Manuel Castilla fue su gran compañero artístico y de correrías nocturnas. Ambos enarbolaban sus obsesiones alrededor de la gente del pueblo, sus leyendas, los oficios, los paisajes. Hay un fuerte pensamiento filosófico en ellos, sus poesías condensan un diálogo con la condición y la finitud humana, al mismo tiempo que los inspira una geografía a la que no renuncian y a la que conocen profundamente.

El Cuchi edificó una obra monumental, más de 800 composiciones, algunas sinfónicas y corales, pero en vida solo grabó dos discos. Siempre se llevó muy mal con las discográficas. Nunca aceptó que le impusieran condiciones leoninas de contratación, y mucho menos limitaciones a su obra. Consideraba que el músico debía encontrar la razón de su música y olvidarse del mercado que constriñe la composición y la embrutece.

Sus composiciones musicales impregnaron de un modo vital todo el folklore argentino, tejiendo un universo de sonidos y de melodías absolutamente novedoso. Supo conjugar las voces anónimas y populares de la música del noroeste con las vanguardias musicales y la sonoridad universal.

El Cuchi Leguizamón fue un hombre multifacético, pero fundamentalmente un músico genial e irreverente. Una figura capital de la música argentina, autor de zambas, chacareras y vidalas de una belleza incomparable. Sus obras son únicas por su armonía y ritmo, su musicalidad y disonancias.

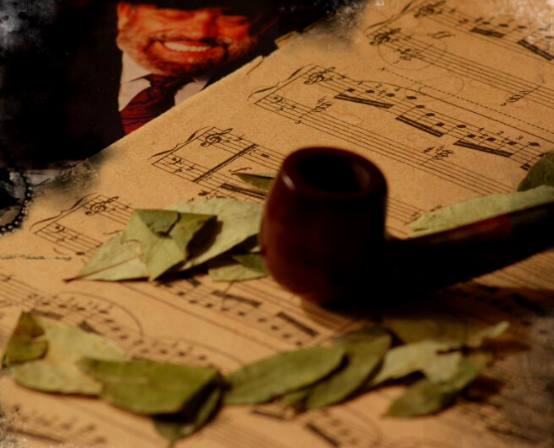

Profundamente aquerenciado a su tierra, el Cuchi formó parte del paisaje de Salta, en los bares que rodean la plaza 9 de Julio, mascando hojas de coca y filosofando, tomando vino o comiéndose «las mejores empanadas del mundo», como solía decir.

Supo retratar a su tierra de una manera que nadie lo hizo. Bohemio y fino pianista, reunió en sus composiciones el toque de un pasado patricio, una erudita formación musical y la cultura popular que cosechó en jornadas regadas de vino tinto junto a Manuel J. Castilla, con el que compuso páginas gloriosas del folklore argentino.

Antes que una enfermedad de años lo sumiera en el olvido, el Cuchi decía: «Si uno pudiera liberarse de la memoria quizá sería posible vivir como los pájaros y también morir como ellos, convertir a la muerte en un hecho natural, en una mansa entrega a la tierra. Pero yo tengo mi mente perjudicada por la filosofía; me resulta imposible dejar de pensar en las cosas que dejo o los que necesitan de mí, y me cuesta aceptar que después de todo la muerte es una aventura hermosa. Siempre me acuerdo de una copla de Castilla que decía: Cuando la muerte venga no le ei de poner asiento/ así no vuelve a venir/ y le sirve de escarmiento.»

Salta es todavía uno de los pocos lugares donde siguen silbando las zambas del Cuchi, sin saber de quién son. «Ese es el elogio más grande que puede recibir un artista”, solía repetir. “Cuando la obra se convierte en anónima pasa a ser parte sustancial del pueblo y no del que la compuso.«

GUSTAVO “EL CUCHI” LEGUIZAMON

(1917 – 2000)

Gustavo Leguizamón was a cultured sensitive man who shone as a pianist and composer, but who was also a talented poet, lawyer, professor and a sharp critic of society.

He was born in the city of Salta in 1917. His father was an accountant and also a huge fan of opera and her mother inherited the unusual but charming habit of whistling to the birds to have them follow her. When he was but a few months old, he worried her parents because of his thinness. Around that time, on one occasion, her mother was offered some pigs to buy. Looking at her son, she exclaimed, “But they are as skinny as this ‘cuchi’ (informally, a pig)!” That is how the boy got his nickname “el Cuchi”, which somehow stuck and stayed with him throughout his life. When he was two years old, Cuchi got measles and his father gave him a “quena” (a typical notched-end Andean flute) to while away the hours in bed. So Cuchi became a “musiquero” (someone who is extremely fond of music) almost before he learned to speak. Afterwards, he taught himself to play other instruments by ear, such as the guitar, the “bombo” (a typical bass drum) and finally the piano.

He was an accomplished musician by the time he was twenty. Despite this, he let his father know that he wanted to study law. The old man was crossed: his plan had always been for his son to continue his musical studies in Paris. However, Cuchi, who took pride in going against rules and conventionalisms, took no heed and moved to La Plata, where he got a law degree.

During his college years, he sang in the university choir and played rugby. Back in Salta, he taught history and philosophy and was also one of the government’s cultural advisers. He also got round to being a member of the province council and led memorable debates in the Legislature to promote what he defined as “brain defrosting.” Keen polemicist and defender of the poor, he used to say, “How can you starve people and believe that we have to walk on the dead bodies of the have-nots so as not to ruffle the feathers of the ‘patria financiera’ (shadow republic of international financiers)?

He loved women in a way that would make any feminist’s hair stand on end; he thought that “an artist’s wife should be a saint in life, that is to say, she should either be a great aristocrat or a wonderful woman of the people.” He also believed that women should “engualichar” or use secret spells when cooking to captivate men as a prelude to dreams and lovemaking. Even though he was a romantic atheist, he married Ema Palermo in church and in time, they had four children.

He was a voracious reader, a “modern” spirit in Salta and a learned man. Throughout his life, he expressed an interest in the manifestations of all artistic avant-garde movements, whereas these happened in literature, music, painting or drama.

Cuchi was a charismatic man who could never be ignored. Ironic and provocative, people say that in times of military dictatorship he was once found reading a book written by Che Guevara in the very select Club 20. He was also a witty teaser and the first one to laugh at his own jokes with a rich contagious laughter.

Cuchi practised law for thirty years until he decided to quit. He explained, “Making music is not enough to earn a living, but it makes me live. This is how things are. When I worked as a lawyer, I lived off discord. Now I live off joy. At my age I have nothing left to do but make music until I have to face nothingness. And I will conquer it because it will be there minding its own business and I will be whistling a tune or other.”

For this man, music had an eminently vital and joyful dimension. He jumped from one stave to the next; he plucked strings; he blew notes on wooden, copper and horn instruments; he pressed piano keys; and all this he did by ear. He also organised concerts in which music was “played” by the tolling of belfries and he tried to put up a similar concert with train engines, which he regarded as “wonderful instruments”. He admired animals too and took the time to listen to their rhythm and melody and learn from them.

His wandering and playful nature drove him to mingle well with popular festivities, their style and “coplas” (popular songs). The relationship and friendship with other poets was another passion. Among these poets, Manuel Castilla became his boon companion in art and nights on the town. They shared the same themes and obsessions: folk people, their legends, their trades, the landscapes around them. Both poets developed a strong philosophy and their poems contain a continual dialogue about the human condition and its finitude and are inspired by a geography which they know extensively and which they never leave.

Cuchi produced a monumental body of work of more than 800 compositions, some of them symphonies and choral music, but in his life he only made two records. He did not get on well with record companies. He could never accept unfair contract terms, and least of all, limitations to his art. He believed that every musician should find the reason behind his music and forget about the commercial market which constraints and dulls composition.

His pieces pervaded the scope of Argentine folklore music, weaving a universe of sounds and melodies which was completely new and refreshingly vital. Moreover, he was able to combine the anonymous voices of the popular music of the northwest of Argentina with the world’s musical avant-garde and the universal sonority.

Cuchi Leguizamón was a multifaceted man, but mainly a brilliant and irreverent musician. He has become a key figure in Argentine folklore, the author of “zambas”, “chacareras” and “vidalas” (all these different typical rhythms) of incomparable beauty. His compositions are really unique for their harmony and rhythm, their musicality and dissonance.

Strongly attached to his native land, Cuchi became one with the landscape of Salta in the bars around the main square 9 de Julio, where he could be seen chewing coca leaves, philosophising, drinking wine or eating “the best empanadas in the world”, as he used to say himself.

He described his land in a way no one had done before. A bohemian and fine pianist, his compositions had the touch of a patrician past, an erudite musical education and the popular culture, which he had absorbed on endless days and nights with Manuel J. Castilla, while they sipped some red wine. Together, they composed some of the most glorious pages in Argentine folklore.

Before a long illness struck him and unfairly consigned him to oblivion, Cuchi once declared, “If we could free ourselves from memories, we might be able to live like birds, and also, to die like them, turning death into a natural fact, a gentle return to the earth. But my mind has been ruined by philosophy: I can’t help thinking about the things I leave behind or those who need me, and I have trouble accepting that, after all, death is a beautiful adventure. I always remember some verses by Castilla which say, ‘When death comes around / I will not offer her a seat / so that she does not come back / and it teaches her a lesson.”

Salta is still one of the few places where people whistle Cuchi’s songs, but they do not know who wrote them. “That is the biggest compliment any artist can receive,” he would repeat. “When a piece becomes anonymous, it also becomes a substantial part of the people and it no longer belongs to its author.”